Melbourne, Australia — The only emperor penguin known to have swum from Antarctica to Australia was released at sea 20 days after he waddled ashore on a popular tourist beach, officials said Friday.

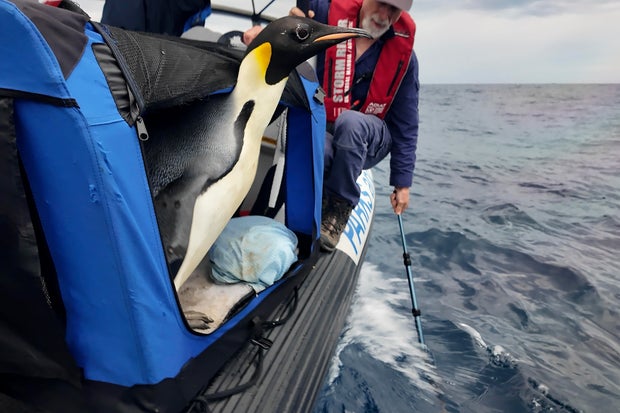

The adult male was found on Nov. 1 on Ocean Beach sand dunes in the town of Denmark in temperate southwest Australia – about 2,200 miles north of the icy waters off the Antarctic coast, the Western Australia state government said. He was released from a Parks and Wildlife Service boat on Wednesday.

The boat traveled for several hours from the state’s most southerly city of Albany before the penguin was released into the Southern Ocean, but the government didn’t give the distance in its statement.

Miles Brotherson /DBCA via AP

He had been cared for by registered wildlife caregiver Carol Biddulph, who named him Gus after the first Roman emperor Augustus.

“I really didn’t know whether he was going to make it to begin with because he was so undernourished,” Biddulph said in video recorded before the bird’s release but released by the government on Friday.

“I’ll miss Gus. It’s been an incredible few weeks, something I wouldn’t have missed,” she added.

DBCA via AP

Biddulph said she had found from caring for other species of lone penguins that mirrors were an important part of their rehabilitation by providing a comforting sense of company.

“He absolutely loves his big mirror and I think that has been crucial in his well-being. They’re social birds and he stands next to the mirror most of the time,” she said.

Gus gained weight in her care, from 47 pounds when he was found to 54 pounds. He is 39 inches tall. A healthy male emperor penguin can weigh more than 100 pounds.

The largest penguin species has never been reported in Australia before, University of Western Australia research fellow Belinda Cannell said, though some had reached New Zealand, nearly all of which is farther south than Western Australia.

The government said that with the Southern Hemisphere summer approaching, it had been time-crucial to return Gus to the ocean where he could thermoregulate.

Emperor penguins have been known to cover up to 1,000 miles on foraging journeys that last up to a month, the government said.

They are among the species directly threatened by the rising temperature of the oceans and seas across the world. According to The World Wildlife Foundation, about three-quarters of the world’s breeding colonies of emperor penguins are vulnerable to fluctuations in the annual sea ice cover in the Antarctic, which have become far more erratic due to climate change.

The penguins breed and live on sea ice, but the Antarctic Sea ice is disappearing as our planet warms up.

“They show up at the breeding season and the ice isn’t there, so they have nowhere to breed,” Dr. Birgitte McDonald, an ecologist at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, which is funded and administered by San Jose State University, told CBS San Francisco last year.

An analysis by scientists at Cambridge University, published last year in the journal Science News, found that “ice in one area was melting especially early in the year,” putting emperor chicks at extreme risk.